(Re)creating new originary identities: the work of Gabriela Morac

11/18/2021

“I am from the zunnî people of Tlacochahuaya, who are you?” Zapotec artist Gabriela Morac, asks us; she makes a visual archeology to reconstruct fragments of her hybrid and ever changing identity through different techniques, such as printmaking and watercolor painting. Her work outlines her intellectual quests for knowledge and historical memory of her culture, while unraveling the language of her intuitive self. Her art reflects on aspects of the huge diversity of the originary cultures of Oaxaca, Mexico.

Born in San Jerónimo Tlacochahuaya, a small town 13.2 miles from Oaxaca city, Gabriela grew up in the countryside, collecting ancestral knowledge while listening to conversations about the Oaxacan sierra and the natural phenomena. Being raised in this context, consequently she was curious about natural sciences like biology and chemistry, and because of her cultural roots, her curiosity also gravitated towards history and archeology. Later in her life, as a means to channel all these interests, she became an artist, after she enrolled in an art course at the Casa de la Cultura Oaxaqueña, which then led her to choose to study at the National School of Plastic Arts at the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

Her techniques and the facets that they reveal

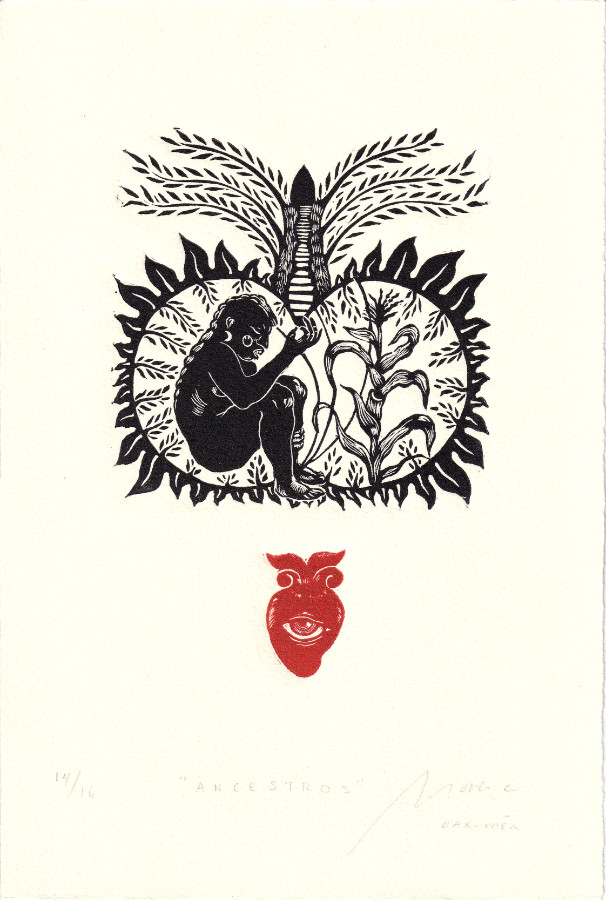

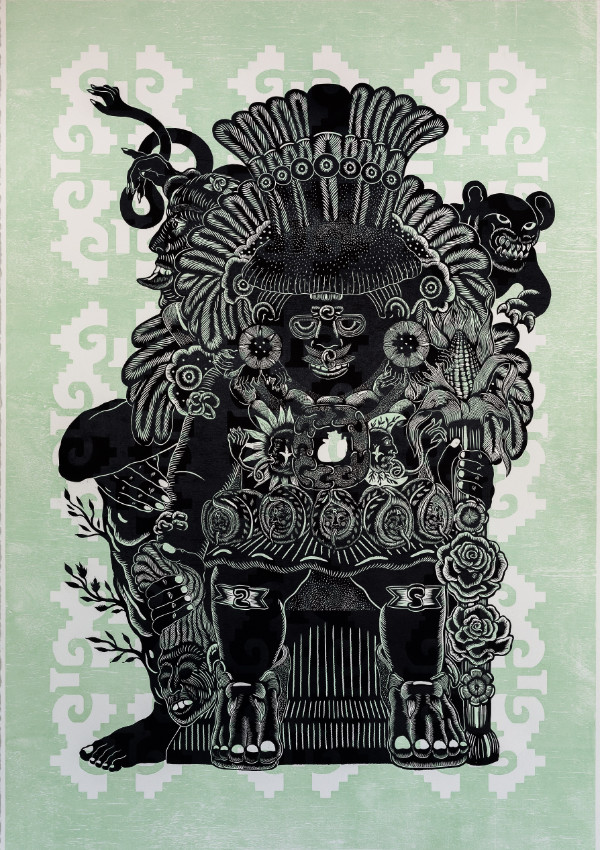

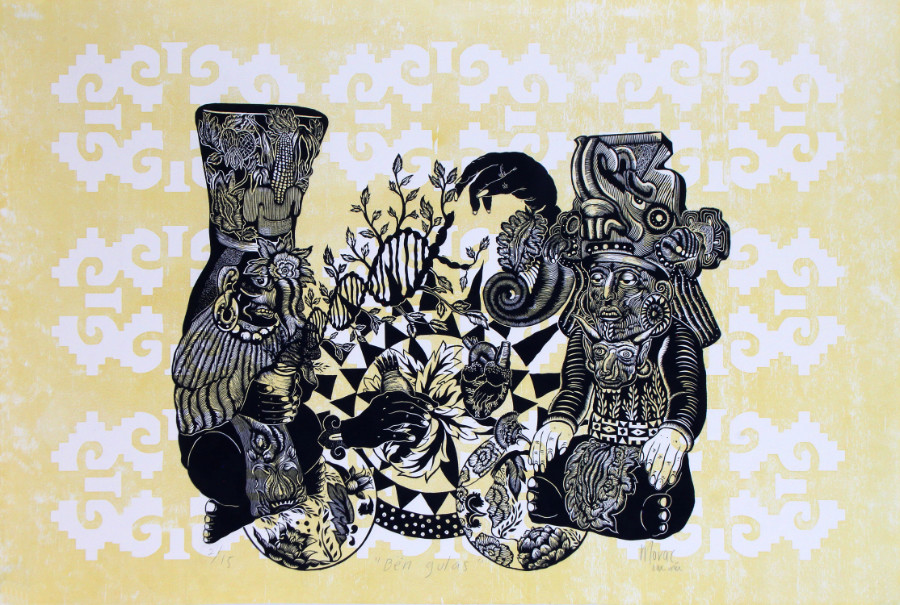

Gabriela describes her work on printmaking and watercolor painting as if each one of them was made by two different people; although both techniques sometimes overlap, each one has opposite outcomes. Printmaking represents her rational self; she plans a lot to create an image. However, she doesn’t sketch: “I like to work directly on the material, I add to and remove from it, depending on what I need. For me, sketching detracts from unity and originality”. Much of Gabriela’s most recent work is based on the reinterpretation of Zapotec pre-Hispanic images. On this basis, each one of her prints has a specifically designed message, which updates and enriches the meaning of old symbolisms.

By contrast, watercolors manifest Gabriela’s intuitive side. For her, painting could be regarded as journaling, in the sense that it is an intimate and recurrent manifestation of her most visceral emotions. She paints a lot, especially when she has a moment of introspection, or when experiencing a difficult emotion, whether it be conflict or uncertainty: “I just take a paper and start to draw, and one thing leads to another, it’s not that I plan to make an image. What needs to come out, comes out; what needs to become an image, flows. My watercolors are a way to transform the uneasiness into something beautiful”.

Beyond Zapotecs, the Zunnîs: the artist’s identitary and historical perspective

Gabriela identifies herself as a Zunnî woman. Zunnîs are the people of (San Jerónimo) Tlacochahuaya, considered one of the first Zapotec settlements in Oaxaca. Their language is Zunnî, which is one of the several variants of Zapotec languages that are spoken in Oaxaca, but, as a matter of fact, the words “Tlacochahuaya” and “Zapotec” come from the Nahuatl language, which was the mother tongue of the Aztecs. After the latter invaded Zunnî territory, in 1486 they named this place Tlacuechahuayan, and their people (as well as other related groups) Zapotecs, these being the terms recorded by the Spanish conquerors. Today, these narratives of domination, control, and colonialism are being rethought by women artists, like Gabriela, changing perspectives through their images, and putting a finger on the fact that gender, language and power are intrinsically related, as anthropologist Aura Cumes points out: “colonialism is patriarchal, and patriarchy is colonial”.

As an artist, Gabriela is interested in reframing cultural and gender identities from a historical perspective, for that purpose, she does plenty of research about Zapotec world views. For many centuries, the Zapotecs (originally named benizáa) controlled the culture, politics and economics of the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, at least from 500 BC to 850 AD. The first representations of their deities date from 1150-850 BC. As Gabriela points out, the fact that the female figure had a great importance in these depictions, reveals the central role of women in those societies.

Creating new images from ancestral figures

Due to her fascination with archeology, Gabriela curates a collection of photos of pre-Hispanic images, especially Zapotec effigy vessels, particularly those that represent Pitaos (divinities). She selects the images intuitively, establishing a dialogue with them, asking them questions: “I look at all the elements that make up the image, I read all the descriptions that I can find about them, and I reinterpret them and rebuild them in a variety of manners, but trying to keep their essential shape”.

During the Colonial Period, in his Zapotec-Spanish dictionary, Fray Juan de Córdova, a Dominican friar, translated Pitao as “God”. In Gabriela’s opinion, this catholic-western interpretation is quite simplistic. Nonetheless, it’s been the most widely used to this day. Rather than represent solely entities or deities, these figures depict a whole philosophy, represented in the multiple symbolisms and elements they contain. There were Pitaos for everything: for the sun, the wind, the rain; for death, for birth, for crops, and so on, because they involved the entire complex dynamics of the energies in the universe.

Depending on which elements she finds in them, Gabriela adds symbols of personal meaning, creating new images. In her artistic explorations, Gabriela takes into account the gestuality of the effigy vessels: legs crossed and hands resting on the knees indicate level headedness; hands holding maize represent an offering gesture. Hands crossed over the chest, mean cherishing; an eloquent gesture, since the heart is so important in the Zapotec language.

The cultural identity carried by the language

The Zapotec language is especially metaphoric; the word “thirst” in English, is translated to Zunnî Zapotec as GhAL RBIz LAaZ (my heart is drying). The ubiquity of the heart as a motif in Gabriela’s work is explained by the fact that a great part of the Zapotec world view is related to this organ, and so are the emotions. She considers herself lucky to have learnt Zapotec as a child; she knows that if she hadn’t learnt it, her interpretation of the world would have been completely different. “Language is the foundation of both knowledge and historical identity”, she emphasizes.

“I don’t like the term ‘indigenous’, I think it is a colonial, despective term; a way to synthesize what is not understood, out of a human necessity to classify everything”, she says. In Mexico, racism, classism and nationalist education projects have facilitated the disappearance of originary languages by encouraging preconceptions about them, and by putting all of them in the unifying category of the “indigenous”. This is reinforced inside the pueblos as well. As the artist says: “as originary communities, we’re reluctant to learn about our own culture. We’re not willing to preserve historical memory, nor cultural heritage, nor pride about our origins”. One of the aims of Espacio Panoplia, a cultural space she runs in Tlacochahuaya since 2016, is to preserve the mother tongue, for that goal she has been working with other colleagues in a project to design didactic prints to teach Zapotec to children.

Gender and eroticism: it’s all about creating life

For Gabriela, eroticism is an important part of human sensibility, it is beyond sexuality, it is more like a non-verbal language. In her work, erotism is manifested through the movement of lines. She conceives eroticism as a subtle energy, from light vibrations of living things to colossal tremblings of the earth. For the artist, the Zapotec language is as poetic as it is erotic, both in meaning and in musicality; for instance, the direct translation for the female genitals is “the place where I become a woman”.

The gender approach in some of Gabriela’s work has to do with the human capacity of creating new beings, and to inherit information, whether cultural or genetic, building bridges between ancient and future eras. The artist states: “though I believe that nature is feminine, there’s a game of complementary binomials -in Zapotec unan (woman) and gul (man)- to generate life”. In her piece “Bën Gulas”, we see Pitao Cozobi (deity of maize), holding a jug with a “blooming” DNA molecule; while the figure in front of her, wearing a skirt with a vulva-like flower and an alligator headgear, is barely touching the genetic “sprout” with one of her three hands. In the artist’s words, this artwork talks about the process of life creation, which involves all the knowledge, beliefs and historical memory that we receive from our ancestors.

The work of Gabriela Morac sheds light on topics about identity that are now more relevant than ever. She examines archeological and anthropological official discourses by juxtaposing contemporary views with antique symbolisms, and thus producing new meanings. Bringing to center stage the importance of cultural and language preservation, she uses art as a research tool to delve into questions about gender, ethnicity, culture, history, biology and the psyche.

View all of Gabriela Morac's artworks.

---

Karina Ruiz Ojeda has a MA in Art History, is an independent researcher, art and music curator. She also teaches Spanish as a second language. She lives and works in Oaxaca City, Mexico.