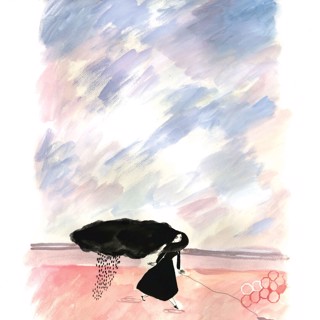

“Until There is Nothing Left to Forgive” is an experience of illustrations, songs and memory created by internationally acclaimed artist Zahra Marwan and renowned soprano and songmaker Tara Khozein.

The tea party-concert-art show is an exploration of Marwan and Khozein’s Persian heritage and their exchange of memories through conversations and writings that have resulted in a collection of paintings and songs.

Memorable exchange: 'Until There is Nothing Left to Forgive' at Harwood Art Center explores Persian heritage through art and song.

“In Kuwait or in Persian culture, people always serve tea in social events, or it’s really common, even when visiting someone, and it’s really thick and dark and small and vibrant and good,” Marwan said. “So we thought we would include that in this collaboration with a traditional (samovar) teapot, which is originally Russian, but has made its way into our cultures for hundreds of years.”

The setting will feature chairs assembled like a traditional Middle Eastern home, which will allow for reflection during the two overlapping 80-minute events at 11 a.m. and 12:30 p.m. on Saturday, Jan. 25, at the Harwood Art Center.

“(The show is) reflecting on what’s been taken from us in various ways, or why our languages have become broken, or why our families had to leave for the reasons that they did, or what it means to hold on to the little things that we still have,” Marwan said.

She illustrates her journey and that of her family through her art.

“I guess they left, like southwestern regions of Iran into Kuwait,” Marwan said of her family. “There was a big migration to work as sea laborers in the early 1900s but then, this shift is what caused, like me personally, statelessness. Racist laws developed of who gets to be a citizen or who doesn’t, and that’s why I immigrated here in the late ’90s.”

Marwan works in watercolor and ink on paper. Her artistic journey began in her early 20s when she moved to Paris and attended a fine art school. She later studied dance in her mid-20s.

“(I) started chronicling these things, and then started chronicling larger ideas of what it means to be a Kuwaiti in New Mexico, and kind of just personally, drawing them and sharing them on social media,” Marwan said. “And then, (I) was surprised that people were resonating with them. I made one book first about this experience, and I think it has done better than I could have dreamed.”

Her book, titled “Where Butterflies Fill the Sky,” published in 2022, was named one of The New York Times/New York Public Library’s 10 Best Illustrated Books, as well as NPR’s Best Books of 2022. Marwan also was honored with an award by the United Nations Human Rights Commission for creating art that brings visibility to “statelessness, Indigenous groups and minority rights.”

“A translation just published in Arabic in Kuwait, which feels miraculous with all the censorship in place or the stigma around statelessness,” Marwan said. “... (It) received an award from the United Nations for bringing visibility to minority issues. And it felt like a strange format to bring attention to something like this, a book of watercolors and lyrical text.”

Marwan and Khozein connected over their shared heritage.

“I’m just such a fan of hers, like I really love her art, and I often kind of develop big artist crushes on people, and then somehow find ways of working with them,” Khozein said. “It turned out that she was really open to doing that with me, and then we just kind of figured out this project together.”

Khozein describes the songs she wrote for “Until There is Nothing Left to Forgive” as theatrical vocal solos.

“They’re unaccompanied and I play a lot with surprise, with comedy, with storytelling, and with all of the different kaleidoscopic colors of the human voice that are sometimes beautiful and sometimes scary and sometimes ugly and sometimes really noisy,” Khozein said. “I guess a lot of my interest in research with a voice is about somehow representing the voice, especially the female voice, as something that can be all of those things. So that’s what I’m exploring in these songs through our shared memories too.”

Khozein’s father and family are from Iran. She said an important part of her identity came from music her family played.

“My uncle is a violinist and his uncle is a violinist,” Khozein said. “He actually played this beautiful Iranian folk instrument called a kamancheh. And so there was just a lot of tea and a lot of sad violin songs in my childhood and adolescence. And I just always really connected to that.”

Article by Albuquerque Journal

View Zahra Marwan's work Here