“Storytelling within Native Hawaiian culture often revolves around layers of deep meaning embedded within pattern symbolism,” says Kanaka Maoli interdisciplinary artist Lehuauakea, explaining that the beautiful patterns and motifs found on things like kapa (barkcloth) and traditional tattoos carry profound significance specific to place, genealogy, personal narrative and more.

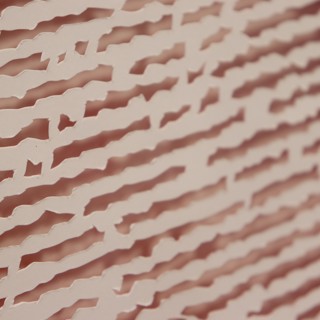

Lehuauakea’s work centers traditional kapa and hand-painted patterns in earth pigments, exploring themes of environmental relations, Indigenous cultural resilience and contemporary Kanaka Maoli identity through these traditional craft practices. Their partner, Ian Kualiʻi, is a self-taught interdisciplinary artist of Kanaka Maoli and Mescalero Apache ancestry who works in murals, large-scale hand-cut paper and site-specific installation, blending urban contemporary art with his ancestral iconography and history. Drawing from occult symbolism, Indigenous politics and Native Hawaiian cultural practices, he creates portraits and compositions from single sheets of paper using only an x-acto blade to render delicate lenticular linework.

Both artists currently split their time between Santa Fe and their ancestral homelands in Hawaiʻi. The title of their upcoming show speaks to their partnership and collaborative relationship, as well as to shared themes of contemporary Native Hawaiian identity in flux, diaspora, cultural reclamation and righting the wrongs of history and (mis)representation.

As an Indigenous artist with deep roots in the urban contemporary art scene, Kuali’i has long incorporated cultural patterns and historical narratives into his paintings and murals. It was through working in mediums like spray paint on concrete walls that he developed the hand cut paper techniques for which he’s become known: he often used paper cutout stencils to create images and motifs. Over time, he began to see the stencil itself as a work of art in its own right and developed techniques to create dimensional imagery.

“I think the process of 'destroying to create' is also close to me on a personal and cultural level,” Kuali’i says. “In Hawaiian thinking, destruction is not necessarily the end of a lifecycle, and is often viewed only as another beginning, like the ferns and plant life that take root in the aftermath of a fresh lava flow. I like to encourage my audiences to think more critically about how they engage with these processes not just by experiencing my work, but within their own lives as well.”

He adds that “By addressing often uncomfortable and overlooked aspects of our shared histories—ones that affect more than just Indigenous or Native Hawaiian communities—we have the capacity to build relationships and understanding founded on truth, which I consider to be a facet of authentic modern progress.”

Ian’s work has recently been acquired by the Hood Museum at Dartmouth College, U.S. Department of the Interior, and the Hawaii State Art Collection.

Lehuauakea’s work, meanwhile, displays their facility with kapa and hand-painted patterns in earth pigments. For this show, they experiment with more unconventional depictions of these patterns, pushing the assumed limits of natural earth pigments by creating undulating gradients.

They came to kapa-making in 2018 while completing their BFA at Pacific Northwest College of Art. Their senior thesis project incorporated the traditional bamboo stamping tools used to print patterns on finished kapa. Through their grandparents, they connected with well-known kapa practitioner Wesley Sen, who had studied alongside many other kapa-makers from around the Pacific during the time of the 1970s Hawaiian Renaissance. “This means a lot to me, not only because our student-teacher relationship keeps this knowledge within our family in a way, but also because in the 'bigger picture' I am entrusted with the responsibility to carry on this knowledge for generations to come,” Lehuauakea says. “The cultural level of responsibility to my community is one of the main driving forces in my work.”

They point out that while there is a resurgence of kapa-making today, the practice had gone largely dormant after Western contact, influence and assimilation threatened this and other traditional practices. “The reclamation and ongoing revival of this alongside other cultural practices is part of the resilience that we as kapa-makers are working to build for present and future generations,” Lehuauakea says. “This in turn fuels an empowered sense of Kanaka Maoli identity, and trickles down into many other facets of everyday life for contemporary Hawaiians.”

Lehuauakea’s work has recently been acquired by the Portland Art Museum, Queensland Art Gallery of Modern Art, and the National Gallery of Victoria.

Both artists navigate a tension between Western and Kanaka Maoli attitudes towards making. Lehuauakea points out that Hawaiian language doesn’t have a word for art because, like many non-Western cultures, ‘art’ is considered to be part of daily life, whether it be utilitarian, spiritual or otherwise.

“Because the foundation of my work is rooted in a traditional practice of making material for clothing, bedding, burials, ceremony, and more, I don't think my practice can be separated from the customary works of my ancestors,” they say. They emphasize the cultural and environmental sustainability of their work, as well as its ties to countless previous generations of knowledge and its position in the ongoing evolution of Native Hawaiian visual storytelling within contemporary Native art as a whole.